Unity by Decree: The Dudley Mosque Merger and the Charity Commission’s Return to ‘Muscular’ Regulation

The Charity Commission’s intervention in the governance of Dudley’s Muslim community represents a definitive pivot in the history of British charity regulation. In January 2026, the regulator announced a move that effectively ended years of administrative paralysis by forcibly merging two disputing entities: the registered Dudley Central Mosque and Muslim Community Centre and an unregistered body known as the Muslim Community Centre and Mosque 1977. This was not a mere administrative tidying of the register; it was an unprecedented deployment of statutory power to resolve “confusion” over day-to-day management by creating a new governing framework “of the Commission’s own motion.” For the wider sector, the significance of the Dudley case is clear: the regulator has shifted from being a passive guide to acting as an architect of a charity’s very existence. This marks the end of an era of infinite patience for factional infighting and signals a return to a “muscular” regulatory stance where institutional survival is prioritised over the internal politics of trustees.

To understand how the Commission arrived at this “unity by decree,” one must first examine the years of administrative collapse and bitter internal friction that left the regulator with little other choice.

The Road to Intervention: Financial Default and Factionalism

The regulatory path to Dudley was paved with years of “double default” status and a persistent refusal to meet basic transparency requirements. While the charity’s last submitted accounts date back to the year ending March 2017, it fell into a state of default beginning with the 2018 accounts. By the time it was placed into the Commission’s “double defaulters” class inquiry in March 2022, it had failed to submit annual reports and returns for four consecutive years. In the eyes of the regulator, these missing accounts were not merely bureaucratic oversights; they were symptomatic of a deeper institutional rot.

Since 2018, the charity has been the subject of three separate regulatory compliance cases. These interventions were attempts to bridge a fundamental divide between two factions claiming to represent the community. In November 2018, the Commission attempted a “lighter touch” approach, providing formal advice to mediate and hold an election overseen by an independent committee. However, this effort collapsed when the resulting election was immediately disputed. Crucially, the legitimacy of the process was undermined by claims from one side regarding a lack of independence within the overseeing committee. When a statutory inquiry was finally opened in July 2022, it was evident that financial non-compliance had become the regulator’s primary gateway to addressing the “factional infighting” that had rendered the organisation’s leadership essentially non-functional.

Section 79(2): Deploying the ‘Nuclear Option’

Faced with a leadership that was “unable or unwilling” to resolve its issues, the Commission deployed what legal observers describe as the “nuclear option” of charity law. In January 2026, the regulator invoked Section 79(2) of the Charities Act 2011 to create a “scheme” to merge the two disputing entities. This move is described by the Commission itself as an unprecedented use of its powers, not applied in such a manner for over 20 years. Typically, the Commission creates schemes only when a charity applies for one by consent; here, it acted entirely of its own motion.

The strategic significance of using Section 79(2) lies in its “surgical” nature. By merging the registered mosque with the unregistered 1977 entity, the Commission was able to “harmonise” the two, incorporating workable elements from both predecessor governing documents into a single, unified framework. This intervention was facilitated by the earlier appointment of an interim manager, Virginia Henley of HCR Hewitsons, in August 2023. Her role provided the Commission with a direct line of communication, bypassing the stalled local leadership to develop a tailored solution. The resulting new Governing Document now exerts strict control over:

- Decision-making processes: Establishing clear protocols to prevent future stalemates.

- Membership criteria and admission: Defining exactly who belongs to the charity to prevent gatekeeping.

- Roles and responsibilities: Explicitly outlining the legal duties of trustees.

- Minute-taking: Standardising administrative transparency.

- Electoral frameworks: Providing a transparent mechanism for the community to appoint future leaders.

While this resolves the structural crisis, it raises significant questions regarding the autonomy of religious associations in the face of state intervention.

Human Rights and the Erosion of Trustee Autonomy

The Commission’s decision to redraft a religious charity’s rules from the top down carries profound legal and ethical weight. As a public body, the Commission is bound by the Human Rights Act 1998 to act consistently with Convention Rights. In this case, the intervention touches upon both Article 11—the right to freedom of association—and Article 9, which protects the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. By “dictating the terms of association,” the regulator has effectively decided for the Dudley congregation what their internal rules are to be.

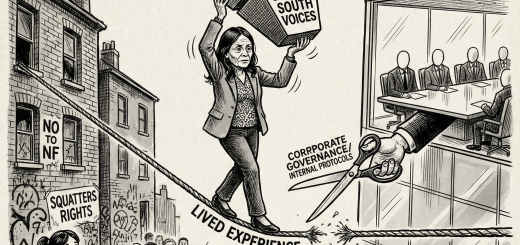

Legal experts warn that this level of control risks eroding the “ownership” and “vision” of the organisation by those who built it. For a religious body, where the governing document often reflects specific theological and community values, having a government regulator include and exclude parts of existing rules is a cause for concern. The Commission is no longer just ensuring the law is followed; it is deciding how people of faith should associate with one another. This loss of internal control is the ultimate price paid for administrative paralysis, a consequence that has its roots in a decades-long struggle over land.

The Ghost of the ‘Super Mosque’: A Legacy of Land and Litigation

At the core of the Dudley fractures lies the failed “Super Mosque” project on Hall Street, a property dispute that served as the primary catalyst for internal division. In 2003, Dudley Council leased the site to the Dudley Muslim Association (DMA) with a “buy-back” clause that required the development to be completed by December 2008. The project became mired in delays, exacerbated by local protests and the council’s initial refusal to grant planning permission—a permission that was only eventually confirmed in July 2009, long after the contractual long-stop date had passed.

A decade of litigation followed. In 2015, an attempt at an out-of-court settlement saw the DMA offer the council £325,000 to drop the buy-back claim. Council bosses rejected the offer, citing a “lack of business planning” and “vague” references to funding. This rejection provided a “smoking gun” for the project’s critics, suggesting that the charity lacked the institutional capacity to deliver on its grand ambitions.

The subsequent legal battle reached the Court of Appeal, which ruled in favour of the council. The ruling provided a vital lesson for the sector: public authorities are entitled to enforce contracts according to their clear terms (such as a buy-back clause) regardless of their own role in project delays, unless bad faith can be proven. The DMA’s “legitimate expectation” defence failed, clarifying that a contract’s terms remain the ultimate authority. This litigation not only drained the charity’s resources but also created a vacuum of leadership that the Charity Commission eventually felt compelled to fill.

Conclusion: A Warning to the Wider Sector

The Dudley Mosque case serves as a stark warning to any charity embroiled in protracted internal conflict. The Charity Commission has demonstrated that its patience with administrative paralysis is finite, and it is now willing to use rarely seen legal powers to impose order where trustees have failed to do so. The “Dudley Model”—appointing an interim manager to bypass stalled leadership and then using Section 79(2) to forcibly rewrite a constitution—is now the established standard “remedy” for such disputes.

Other organisations must learn that failing to engage in genuine mediation or neglecting basic financial transparency can lead to a total loss of governance autonomy. In Dudley, the quest for a new community hub ended not with a grand opening on Hall Street, but with a regulator-imposed merger and a constitution written in London. It is a sobering reminder of the new reality: if a charity cannot govern itself, the state will step in to do it for them.